Once upon an amalgam…

…a wise old wolf gave each of his three pigs a bag of talents. Two of the wicked stepsisters – their names were Goneril and Regan – were lazy and stupid and built their houses out of straw and sticks. So no matter how much the Big Bad Lear huffed and puffed, he couldn’t get the glass slipper to fit on a single foot, for the first bag of talents was way too hot and the second was far too soft.

But Cordelia’s bag of talents was just right, for she had built hers out of bricks.

So when Papa Lear found Cinderella sleeping in his bed, he cried, “Nothing will come from nothing,” and added, “Thou wicked and slothful servant, cast ye into outer darkness: there shall be weeping and gnashing of teeth.”

And he married her and they all lived happily ever after. The End.

This is what happens after you’ve read enough Finnegans Wake; stories become confounded and start blending together, especially if they exhibit even slight similarities. Matthew 25:14-30 melds into act I scene 1 from King Lear, who then becomes the Big Bad Wolf, who then somehow fits a glass slipper onto Cinderella, who in her turn becomes Goldilocks and so on. Distinctions such as ‘happy ending vs unhappy ending’, ‘wolf-and-pigs vs father-and-daughters’, ‘bags-of-talents vs bowls-of-porridge’, et cetera start to matter much less than the structural scaffolding these stories are all built on, for the pattern is unmistakably predictable:

- Once upon a time, a thing happened.

- As a result, three things happened, one after the other.

- The first thing was a thing, and it went POW.

- The second thing was a different thing from the first thing, but not really, for it also went POW, or maybe KA-POW.

- But the third thing was a totally different thing, and it went BOOM, or maybe WHOOSH or THUD.

- And we all learned a new thing. The end.

Apply this outline to any of the stories referenced in my little amalgam and they all fit, without exception. A whole bunch of others do as well – here’s just one example:

- Once upon a time, a thing happened.

A giant beanstalk grows in Jack’s back yard. - As a result, three things happened, one after the other.

Jack climbs/descends the beanstalk three times. - The first thing was a thing.

Jack steals a bag of gold, “Fee-fi-fo-fum” etc. - The second thing was different but not really.

Jack steals the golden goose, “Fee-fi-fo-fum” etc. - But the third thing went BOOM / WHOOSH / THUD.

Jack steals the magic harp, which cries out (BOOM), the giant chases Jack (WHOOSH), who chops down beanstalk (THUD). - And now it’s a new thing.

Jack and his mother are rich and never have to work again.

Sometimes called the Rule of Three, this storytelling trope is pretty much the oldest one in the book, and it’s used and re-used by writers to this very day. It arguably plays roles in Freytag’s pyramid, Campbell’s hero-journey, and perhaps even Aristotle’s formula for successful drama, vide his great exemplar, Sophoceles’ Oedipus Rex:

- Once upon a time, a thing happened

Oedipus vows to find Laius’ killer. - As a result, three things happened, one after the other

Three old men are summoned to testify. - The first thing went POW

The first old man (Tiresias) implicates Oedipus as the killer. Oedipus responds with threats. - The second thing also went POW

The second old man (first shepherd) gives evidence further implicating Oedipus, who responds with more threats. - But the third thing went BOOM

The third old man (second shepherd) confirms the guilt of Oedipus, who responds by blinding himself. - And we all learned a new thing

Destiny is a bitch.

(MacBeth comes to mind here as well, with the three witches and their whole Glamis/Cawdor/King business.)

So with such literary heavies as Sophocles and Shakespeare (as well as Dante, come to think of it) weighing in, James Joyce certainly wouldn’t allow himself to be left out. He enters into this fray with an eye to creating a very specific effect, however, and so adds his own set of rules to the trope’s makeup. I call it the “Prankquean Matrix” to distinguish it from the general “rule of three”, and I take my moniker from one of the more celebrated passages in Finnegans Wake…

…and it goes a little like this:

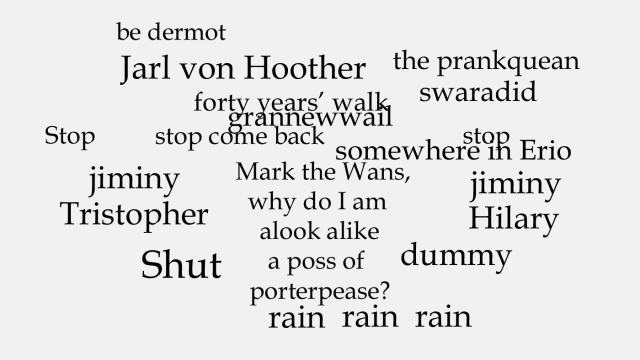

JoyceGeek Presents: The Prankquean Video

JoyceGeek Presents: The Prankquean Video

Sure, the language here is difficult – it’s Finnegans Wake after all. But knowledge of the source material Joyce used for this passage (Grace O’Malley & the Earl of Howth, St. Patrick & the druid, Grania & Dermot, etc.) is hardly a prerequisite for understanding pp. 21-23 (though it’s certainly always a good thing to have). Every bit as simple as ‘Jack and the Beanstalk’, the story’s structural breakdown is almost sophomoric:

- Once upon a time, a thing happened

Jarl von Hoother is holed up with his three charges: the jiminy Tristopher, the jiminy Hilary, and the dummy. - As a result, three things happened, one after the other

The Prankquean riddles Jarl and kidnaps his charges. - The first thing went POW

“Mark the wans” etc. Jarl shuts the gates, the prankquean nabs jiminy Tristopher. - The second thing also went POW

“Mark the twy” etc. Jarl shuts the gates again, the prankquean nabs jiminy Hilary. - But the third thing went BOOM/WHOOSH/THUD

“Mark the tris”etc. (the prankquean is presumably about to nab the dummy), Jarl is provoked / Thunder. - And we all learned a new thing

The fable concludes with a number of “morals”.

So leaving aside the typically impenetrable linguistic details, what we have here is almost pure archetype, and if we want to suggest an avatar for the trope as Joyce used it, the distorted language actually serves to create some critically helpful ambiguities:

- Is it a happy ending?

No telling. - Which character is the villain, which the hero?

Again, no telling. - Is the Moral’s tone cautionary or simply observational?

Perhaps both, perhaps neither.

The only unambiguous issue here is gender – a female (prankquean) provokes a male (Hoother) three times etc – and with one single exception (that I could find), Joyce assigned these specific gender roles each and every time he incorporated the ‘rule of three’ into his writing. The exception can be found in the following extremely subtle example which, as always, Joyce created to a purpose:

from A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man:

(The prankquean matrix pattern will become much more blatant as we progress through more examples, but uncovering its subtle occurrences in Joyce can be as fun a parlor-game as finding the H.C.E. acrostic in Finnegans Wake.)

Immediately before Stephen Dedalus vomits “profusely in agony” in chapter three, he imagines the demons of his Roman Catholic Guilt following a “hither and thither” pattern. This phrase: “hither and thither” – which I’ve highlighted in red below – is repeated exactly three times, and will be later developed into something of a leitmotif in Joyce’s other works:

—Creatures were in the field: one, three, six: creatures were moving in the field, hither and thither. Goatish creatures with human faces, hornybrowed, lightly bearded and grey as india-rubber. The malice of evil glittered in their hard eyes, as they moved hither and thither, trailing their long tails behind them. A rictus of cruel malignity lit up greyly their old bony faces. One was clasping about his ribs a torn flannel waistcoat, another complained monotonously as his beard stuck in the tufted weeds. Soft language issued from their spittleless lips as they swished in slow circles round and round the field, winding hither and thither through the weeds, dragging their long tails amid the rattling canisters. They moved in slow circles, circling closer and closer to enclose, to enclose, soft language issuing from their lips, their long swishing tails besmeared with stale shite, thrusting upwards their terrific faces . . .

—Help!

This rather ‘goth’ passage takes place near the novel’s center, at a point where Stephen’s aesthetic is still very much in incubation. As Stephen matures, the narrative associations in the novel mature as well, so that by the end of the fourth chapter, we have a near perfect inversion of the above passage, again with a threefold repetition of “hither and thither”, and again followed immediately by a foundation-shaking catharsis:

—She was alone and still, gazing out to sea; and when she felt his presence and the worship of his eyes her eyes turned to him in quiet sufferance of his gaze, without shame or wantonness. Long, long she suffered his gaze and then quietly withdrew her eyes from his and bent them towards the stream, gently stirring the water with her foot hither and thither. The first faint noise of gently moving water broke the silence, low and faint and whispering, faint as the bells of sleep; hither and thither, hither and thither; and a faint flame trembled on her cheek.

—Heavenly God! cried Stephen’s soul, in an outburst of profane joy.

The larger sections of which these two passages are a part also invite careful cross-comparison. Both are stunning outpourings of lyrical prose with near identical syntax and rhythm, and as the above examples demonstrate, the vocabulary even matches from time to time. One could argue that the second passage simply sublimates the first.

But this is more than mere sublimation. The girl in the stream – much like Dante’s Beatrice – is a kind of herald, trumpeting a permanent associative shift in Joyce’s prose. From this point on, Stephen (and Joyce by proxy, of course) will hold fast to two basic associations:

- The phrase “hither and thither” will be used exclusively to invoke the feminine and/or water.

- The ‘rule of three’ trope will be used exclusively to describe a female-to-male interaction as defined by the Prankquean Matrix.

(This blogpost is all about association #2, of course, but very quickly: the “hither and thither” examples to which I refer are mostly from Finnegans Wake: p. 158 lines 25 & 32, p. 216 line 4, p. 452, lines 27-28, etc. There is at least one from Ulysses as well, though: Gabler ed. p. 288, line 626.)

So turning to Dubliners…

(… and yes, I know, Dubliners is an earlier work than Portrait. I place it later in my mind because I assume it to have been composed by a post-Portrait Stephen Dedalus, i.e. a matured Joyce who has already worked out his aesthetic guidelines.)

Three-fold female-to-male interactions are everywhere in Dubliners, and often constitute the structure of entire stories. Here are just a few examples:

Counterparts

- Three things happen, one after the other:

Farrington (male) is denied access to three females: Miss Delacour, the nameless London woman, and Mrs Farrington - The first thing went POW:

Miss Delacour smiles broadly / Farrington is emboldened. - The second thing went KA-POW:

London woman brushes past Farrington / Farrington is aroused. - But the third thing went BOOM:

Mrs Farrington goes to the chapel instead of cooking dinner / Farrington is enraged. - And now it’s a new thing:

Farrington beats his son.

Clay

- Once upon a time, a thing happened:

The Donnellys throw a Hallow’s Eve party.. - As a result, three things happened, one after the other:

Maria (female) embarrasses herself three times in front of Joe Donnelly (male). - The first thing went POW:

Maria loses the plumcake and nearly cries outright / Joe comforts her. - The second thing went KA-POW:

Maria suggests a reconciliation with Alphy / Joe rebuffs her. - But the third thing went THUD:

Maria sings poorly / Joe is moved, becomes maudlin, weeps. - And now it’s a new thing:

Joe’s corkscrew is missing.

The Dead

- Once upon a time, a thing happened:

The Misses Morkan host their annual dinner. - As a result, three things happened, one after the other:

Three females (Lily, Miss Ivors, Gretta) provoke Gabriel Conroy. - The first thing went POW:

Lily: “The men that is now is only all palaver” etc. / Gabriel is irritated. - The second thing went KA-POW:

Miss Ivors: “West Briton!” / Gabriel is aggravated. - But the third thing went BOOM:

Gretta: “I think he died for me.” / Gabriel is devastated. - And now it’s a new thing:

Generous tears, etc.

All of these stories adhere to Joyce’s prankqueanish gender assignments – females provoking males. They are all neatly divided into three sections: ‘Counterparts’: work / pub crawl / home, ‘Clay’: work / shopping-spree / party, ‘The Dead’: before / during / after dinner. And seemingly random references to the number three are almost comically ubiquitous throughout all of these stories: Farrington’s son offers to “say a Hail Mary” exactly three times, during the course of ‘Clay’ exactly three items are lost and Maria’s nose is described as nearly touching her chin exactly three times, and Gabriel famously toasts “the Three Graces (Joyce’s capitalization) of the Dublin musical world”. These occurrences are prankquean obliques – not examples of the prankquean trope by themselves but merely signals of her matrix’s presence.

There are many more prankqueanish instances in Dubliners than just these three, but these are the most obvious, and three, after all, is the magic number here. I’ll save the other Dubliners examples for a later post.

Moving onto Ulysses…

The opening of the ‘Calypso’ chapter has a rather cute exchange:

- Once upon a time, a thing happens:

It’s breakfast time. - As a result, three things happen, one after the other:

The cat (female) approaches Bloom (Male) “with tail on high”. - The first thing goes:

“Mkgnao!” / Bloom offers milk. - The second thing goes:

“Mrkgnao!” / Bloom withholds milk, taunting the cat. - But the third thing goes:

“Mrkrgnao!” / Bloom pours the milk. - And now it’s a new thing:

“Gurrhr!”

This exchange appears to be a trivialization of the pattern, but notice: the cat’s vocalizations are not mere repetition. Each one builds off of its predecessor, inserting a vocal “r” with each new utterance. Had Bloom continued to withhold milk, we can assume the fourth would be “Mrkrgrnao!” As is typical with Joyce, however, the pattern breaks after three.

It’s worth noting that the cat’s mewing sound ends each time with “nao”, a sound to be echoed later – and again thrice – by young Tommy Caffrey at the beginning of the ‘Nausicaa’ chapter:

—Tell us who is your sweetheart, spoke Edy Boardman. Is Cissy your sweetheart?

—Nao, tearful Tommy said.

—Is Edy Boardman your sweetheart? Cissy queried.

—Nao, Tommy said.

—I know, Edy Boardman said none too amiably with an arch glance from her shortsighted eyes. I know who is Tommy’s sweetheart. Gerty is Tommy’s sweetheart.

—Nao, Tommy said on the verge of tears.

Now this is true trivialization: no signs of change nor accrual from one instance to the next, and apart from the narrative shift to Gerty, nothing significant happens as a result, certainly not ‘BOOM’. So this doesn’t really qualify as a true prankquean exchange. Rather, this passage is another prankquean oblique – a signal to be on the lookout for the true pattern in the pages to come, and sure enough, careful scrutiny reveals the following:

- Once upon a time, a thing happens:

Gerty (female) and Bloom (male) are on the beach in Sandymount. - As a result, three things happen, one after the other:

Gerty reveals herself to Bloom in three different ways. - The first thing goes POW:

She kicks the ball and makes eye contact with Bloom. - The second thing goes KA-POW:

She removes her hat and reveals her hair, “raising the devil” in Bloom. - But the third thing goes BOOM/WHOOSH/THUD:

She arches back to reveal her knickers. Bloom bastes his loins. - And now it’s a new thing:

“Cuckoo Cuckoo Cuckoo” (3x)

All of this is of course merely prep-work for the ‘Circe’ chapter, which works countless prankqueanish echoes and variants into its narrative, from the three wealthy socialites of Bloom’s hallucination (Mrs Bellingham, Mrs Yelverton Barry and the Honourable Mrs Mervyn Talboys) to the three whores whom he and Stephen encounter in the flesh (Zoe, Kitty and Florry). Nothing in ‘Circe’ is clean, however, so the pattern doesn’t seem to take a solid hold here as it does elsewhere, although certainly the apparition of Stephen’s mother feels very much like ‘the third thing that goes BOOM’. Plus, it can hardly be mere coincidence that the mother’s appearance comes as a near-direct consequence of the pianola’s playing “My Girl’s A Yorkshire Girl“, a song in three-quarter time with three verses about three men who share a single woman. If this isn’t enough to establish Joyce’s commitment to the pattern, nothing is.

So then, back to the Wake.

A major problem arises with what properly should be the Pankquean Matrix’s ultimate expression: Finnegans Wake pp. 219-259, “The Mime of Mick, Nick and the Maggies” (Joyce’s own title). It’s a chapter rife with Prankquean signposts: It culminates with a thunderword (#7) and concludes with overtones of a “moral” – the final sentence of the chapter being one of the most lauded in the entire book. And it contains numerous threefold interactions between male and female, most notably on page 225:

—Have you monbreamstone?

—No.

—Or Hellfeuersteyn?

—No.

—Or Van Diemen’s coral pearl?

—No.

…repeated with a difference on page 233:

—Haps thee jaoneofergs?

—Nao.

—Haps thee mayjaunties?

—Naohao.

—Haps thee per causes nunsibellies?

—Naohaohao.

This last interaction is of course famously evocative of tearful Tommy Caffrey’s exclamations in ‘Nausicaa’, and much like Bloom’s cat, develops a phonetic accrual from one utterance to the next.

So you may be well asking the same question Wake scholars have been asking for three-quarters of a century now: With the first exchange from p. 225 looking an awful lot like the thing that goes POW, especially when paired with the KA-POWish one on p. 233, where’s the third exchange preceding the BOOM on p. 257?

Answer: there is none.

…at least none that the scholars can agree on. One of my favorite Wake scholars, John Gordon, sees it happening on p. 247:

—Boo, you’re through!

—Hoo, I’m true!

—Men, teacan a tea simmering, hamo mavrone kerry O?

—Teapotty. Teapotty.

—Kod knows. Anything ruind. Meetingless.

I’ve also heard it argued that it takes place on p. 249:

—I rose up one maypole morning and saw in my glass how nobody loves me but you. Ugh. Ugh.

—All point in the shem direction as if to shun.

—My name is Misha Misha but call me Toffey Tough. I mean Mettenchough. It was her, boy the boy that was loft in the larch. Ogh! Ogh!

A great many scholars, including Bernard Benstock, Margaret Solomon, Grace Eckley, and Danis Rose all argue that it takes place on page 250:

—Willest thou rossy banders havind?

—He simules to be tight in ribbings round his rumpffkorpff.

—Are you Swarthants that’s hit on a shorn stile?

—He makes semblant to be swiping their chimbleys.

—Can you ajew ajew fro’ Sheidam?

—He finges to be cutting up with a pair of sissers and to be buytings of their maidens and spitting their heads into their facepails.

Still others place it on p. 252:

—Now may Saint Mowy of the Pleasant Grin be your everglass and even prospect!

—Feeling dank.

—Exchange, reverse.

—And may Saint Jerome of the Harlots’ Curse make family three of you which is much abedder!

—Grassy ass ago.

And Roland MacHugh, perhaps more persuasively than anyone else, claims in his Annotations (with Slepon chiming in as well) that the final exchange is on p.253:

But Noodynaady’s actual ingrate tootle is of come into the garner mauve and thy nice are stores of morning and buy me a bunch of iodines.

—Evidentament he has failed as tiercely as the deuce before for she is wearing none of the three.

While there are good arguments for all of these speculations (and probably more), I think they’re all likely fueled by little more than a desire for the pattern to be completed. Joyce has, of course, quite deliberately built up these expectations over the course of four novels, but his writing really only ever consistently follows one rule, and here it is:

Rules are for breaking.

The ‘Mime’ chapter is, after all, a study of childhood, and children never respond to rules very well.

This, in my view, is the ultimate function of the Prankquean Matrix. The vast majority of examples from Joyce’s works I’ve cited here involve the male figure experiencing a disruption of one kind or another – of routine, of agenda, of rigid thought-pattern. In this sense, the Prankquean Matrix actually functions as more of a formula for change than it does a trope for storytellers, and this is the reason I believe Joyce so consistently assigned a feminine/puerile value to the disruption. Women and children may be first onto the lifeboats, but in a world ruled by men, they are the marginalized, inconvenient voice of the other that need only be pushed aside in order to go boom.