Go, Set, Ready!

There are lots of ways to read Joyce, and really, none of them are conventional.

After all, Joyce’s writing remains outside even today’s boundaries of convention – a full century later. So for the nonce (but not really), I’d like to recommend the following programme: Start by reading Finnegans Wake, and when that’s done, read Ulysses, then A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, and finally Dubliners. Do this as if these books were written in this order, as if they were intended to be read in this order, as if this were their natural order of ascending complexity, and no fool in their right mind would dare even crack open Dubliners without first having fully immersed themselves in the later works – particularly Finnegans Wake.

It’s a little something I like to call Reverse-Reading, a practice that brings insights into the earlier works that quite simply would not be possible otherwise. I wouldn’t be surprised actually if the term has been used before, for the practice itself certainly has. Some of my favorite Dubliners studies are in fact by Finnegans Wake scholars: John Gordon and Margot Norris come immediately to mind (links are to the books I recommend). John’s wonderfully dense reading of A Little Cloud pairs itself beautifully with the “Issy” character outline in Finnegans Wake, and Margot has a brilliant Reverse-Reading of Two Gallants that places the events it describes after those of Ulysses – as if it were a sequel. Plus, a great many Wake scholars – John and Margot included – have observed that the washerwomen of Finnegans Wake who “tuck up” their sleeves as they prepare for their day’s work at the beginning of chapter 8 (FW196.8) are later seen “pulling down” those same sleeves as they come in from their day’s work at the beginning of Clay.

I discovered a pretty amazing Reverse-Reading of my own a while back – it’s of a single short story, the second in the Dubliners collection – An Encounter. The story itself is a short and simple read – one of the quickest in the book – and while it is celebrated for its visceral depiction of youthful awakenings, it’s often misunderstood as one of the “lesser” Dubliners installments, generally when compared to Araby, A Little Cloud, The Dead, etc. A straightforward Reverse-Reading of An Encounter from a Wakean should hopefully – well – reverse this misconception.

So why is this story so often marginalized? Most complaints center around the seeming lack of structure. An Encounter is a bit of a structural salmagundi for non-Wake readers; as John Wyse Jackson and Bernard McGinley so well observe (p. 20):

…this is not one story, but two half-stories. A narrative that starts out about the Dillon brothers loses one of them, then the other: the business of miching from school is then bolted on to the account of the strange meeting. Most exasperating of all, [the story has] no conclusive ending. The inconclusive petering out shows how much Joyce needed catching up with by the contemporary reader. He still does.

“Contemporary readers” might very well be stumped, but none of these “inconclusive peterings-out” should hold the least amount of concern for the Finnegans Wake reader. Conclusive endings? Who needs endings at all? Half-stories bolted together? Pshaw – try half-words bolted together. And so what if Joe Dillon is completely vanished from the narrative before the first page is half-over? Do Wake readers care that “Sir Tristram, violer d’amores,” the first character to be introduced in Finnegans Wake (3.04), makes no further appearance? Hardly.

For one thing, “Sir Tristram” doesn’t really vanish at all – his ‘love-violations’ continue deep into the book and even build in scope – it’s only his name that changes. Granted, his name changes a lot – at every available opportunity in fact – as many as five times within the book’s first full paragraph alone: “topsawyer’s rocks”, “tauftauf thuartpeatrick”, “a bland old isaac”, “twone nathandjoe”, “Rot a peck of pa”, etc. In Joyce’s world, characters are identified by their actions; names are as interchangeable as playing cards.

This program of identification is not arbitrary randomization – it has movement toward a purpose, and is key to understanding Joyce’s revolutionary method of character development, which he actually gives a name to in Ulysses:

METEMPSYCHOSIS

That’s right – Metempsychosis – the only ten-dollar word in Ulysses that you don’t have to look up in the dictionary, for Leopold Bloom himself gives it a full and extended definition in the ‘Calypso’ chapter: reincarnation, “the transmigration of souls”, the phenomenon whereby an individual’s psychological value is transferred from one persona to another. This is how Cranley from A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man can transmigrate to Buck Mulligan in Ulysses and then on to Shaun the Post in Finnegans Wake, for example. My favorite description of how the transmigration works comes from Ananda K. Coomaraswamy* who, like Bloom, ties the concept of transmigrating to that of karma:

[Imagine] a series of billiard balls in close contact: if another ball is rolled against the last stationary ball, the moving ball will stop dead, and the foremost stationary ball will move on. Here precisely is Buddhist transmigration: the first moving ball does not pass over, it remains behind, it dies; but it is precisely the movement of that ball, its momentum, its karma, and not any newly created movement, which is reborn in the foremost ball. […] Nothing is transmitted but an impulse, a vis a tergo, dependent on the heaping up of the past. It is a man’s character, and not himself, that goes on.

[Imagine] a series of billiard balls in close contact: if another ball is rolled against the last stationary ball, the moving ball will stop dead, and the foremost stationary ball will move on. Here precisely is Buddhist transmigration: the first moving ball does not pass over, it remains behind, it dies; but it is precisely the movement of that ball, its momentum, its karma, and not any newly created movement, which is reborn in the foremost ball. […] Nothing is transmitted but an impulse, a vis a tergo, dependent on the heaping up of the past. It is a man’s character, and not himself, that goes on.

*Buddha and the Gospel of Buddhism, pp. 107-108. The original “new age” movement, spearheaded by Coomaraswamy, Helena Blavatsky, W. B. Yeats, Lady Gregory et al was very much en vogue in Dublin during the period of An Encounter‘s composition, and while Joyce couldn’t ultimately stomach all of the mystical mumbo-jumbo, he did spend some time studying it; he was even seen walking about Dublin carrying a copy of H. S. Olcott’s Buddhist Catechism as if he were a clergyman carrying a prayerbook.

Returning to An Encounter, Joe Dillon does indeed appear to completely vanish from the story with a simple two-sentence paragraph:

—Everyone was incredulous when it was reported that he had a vocation for the priesthood. Nevertheless it was true.

Appearances can deceive, however. True, Joe Dillon – much like the billiard ball in Coomaraswamy’s metaphor – has been ‘stopped dead’; it’s as if entering the seminary is tantamount to a death sentence in fact, for no further mention is given to Joe or his “war dance of victory”. But even here in this brief half-page of text, Joe Dillon’s actions have already ‘heaped up’ enough momentum so that the karmic impulses he started – a morbid blend of aggression and piety – are easily transmitted to the character of Father Butler on the following page, who, though he no longer wears a tea cozy on his head shouting “Ya! yaka, yaka, yaka!”, is indeed found humiliating his students as he teaches them Julius Caesar’s Commentaries on the Gallic Wars as if he expected them to memorize it:

—This page or this page? This page? Now, Dillon, up. Hardly had the day… Go on! What day? Hardly had the day dawned… Have you studied it? What have you there in your pocket?

No simple change of plotline can eliminate the influence of this future priest; it remains ubiquitous throughout the story: Mahoney bullies the smaller children in the street in likely response to being bullied himself by the even bigger Joe Dillon. The narrator’s haughty attitude towards “National School boys” is lifted directly from Father Butler’s ‘rebuke’, and Leo Dillon’s cowardly choice to forgo the miching adventure is influenced most likely by both brother and priest. Mahoney’s question, “what would Father Butler be doing out at the Pigeon House” is not nearly so rhetorical when viewed in this light.

Like Joe before him, younger brother Leo Dillon is also expelled from the narrative after brief prominence as its central figure. This second disappearance raises the question as to whether Leo’s character transmigrates as well, and again, if we look to the behavior patterns, especially the specific role Leo plays up to the point the other boys abandon him, I believe that an answer reveals itself. One has almost to look twice at the phrase: “…the confused, puffy face of Leo Dillon awakened one of my consciences” to notice that the word employed here is ‘consciences’ rather than ‘consciousness’. On the surface at least, consciousness would be a much tighter semantic fit given its pairing with ‘awakened’. But the story’s central issue has less to do with awareness per se than than it does with moral rectitude. After all, An Encounter‘s final sentence shows us a ‘penitent’ (i.e. ‘conscientious’) narrator – the direct result of having seen another ‘confused’ face, this time with “bottle-green eyes peering…from under a twitching forehead.”

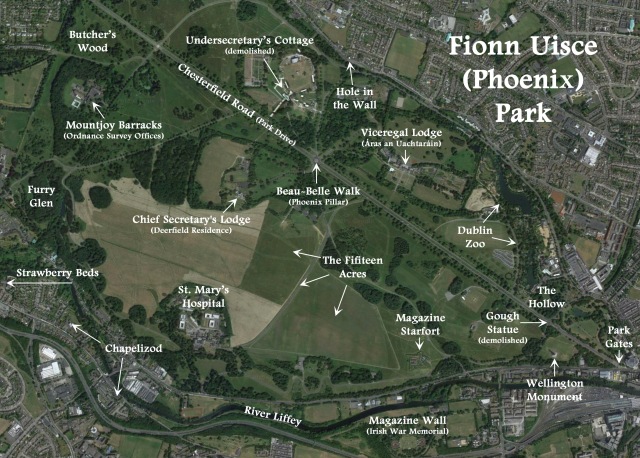

Evidence that this nameless and deeply troubled stranger in the field at Ringsend is the abandoned and transmigrated soul of Leo Dillon, though perhaps less direct than Joe’s vocational connection, nevertheless abounds. Soon after his appearance, the stranger’s behavior is observed as unusual: “I wondered why he shivered once or twice as if he feared something…” As his attitude is “strangely liberal,” maybe this phantom fear is of humiliation or castigation from the likes of Father Butler or Mr. Ryan. That “his accent was good” indicates higher, perhaps Jesuitical education, but the strongest argument for the stranger’s metempsychotic link to Leo Dillon is his warped sexuality and sadism, which could easily be an advanced stage of what originated in childhood as overeating, idleness, and inability to adapt to an environment of constant bullying, derision, and oppression.

So next question: is there a third? This is after all a story about childhood, and children’s stories invariably require a third occurrence in order to reach completion. In fact, the story itself seems to be keenly aware of what has come to be commonly known as the “Rule of Three“:

When we came to the Smoothing Iron we arranged a siege; but it was a failure because you must have at least three.

The story’s third banishment is of course Mahoney, who, when he runs off to chase the cat, disappears from the narrative much like the Dillon brothers before him. For a full two pages – taking us nearly all the way to the end of the story – the young narrator’s interaction with the pedophilic stranger so completely dominates the narrative that Mahoney himself seems to forget he’s still part of it:

—Murphy!

—My voice had an accent of forced bravery in it, and I was ashamed of my paltry stratagem. I had to call the name again before Mahony saw me and hallooed in answer.

Note that for a moment at least, Mahoney here becomes ‘Murphy’, a very brief identity-shift which, while it falls just short of outright Dillon-style metempsychosis, nevertheless touches on the story’s pattern of exile and transformed return. This is not just a clever storytelling trick – it actually points us toward the nature of the narrator’s final penitence, the real karmic momentum of An Encounter which has been accrued not by Mahoney nor even the Dillon brothers, but by the narrator himself. It is the narrator’s personal agenda – his longings for a sense of personal agency, for adventure abroad, for distinction from the common rabble – that drive the plot forward. Notice, too, that in the three stories which he narrates, we never learn his real name – the only name we’re ever given is a pseudonym – ‘Smith’:

—In case he asks us for our names, I said, let you be Murphy and I’ll be Smith.

The good Reverse-Reader should here recall the finale of A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, where Stephen Dedalus, obviously one-and-the-same as the narrator of the first three Dubliners stories, likens himself to a blacksmith in the novel’s penultimate sentence, and note once again how Joyce slyly invokes moral rectitude by swapping the word ‘consciousness’ with its phonetic double, ‘conscience’:

I go to encounter for the millionth time the reality of experience and to forge in the smithy of my soul the uncreated conscience of my race.

Awe-inspiring though Stephen’s declaration here may be, it is also dangerously arrogant – bordering on self-apotheosis – and contains within it a seed of his Icarus-like fall in Ulysses. Who is this young upstart to claim he can create his race’s conscience? Even given such a power, what’s to prevent him from abusing it? It is the narrator himself who ejects the Dillon Brothers and Mahoney from his story, and his motivation for doing so should be obvious: this is his adventure, and he’ll do whatever it takes to eliminate any and all rival protagonists. Ethically, his actions are highly questionable; he in fact commits all three types of “sin” as defined by the Catholic church:

- Sin by thought:

Elitism and bigotry; “I was afraid the man would think I was as stupid as Mahony.”

- Sin by word:

Malice and gloating: “We revenged ourselves on Leo Dillon by saying what a funk he was and guessing how many he would get at three o’clock from Mr. Ryan.”

- Sin by deed:

Deception and theft: He pockets Leo Dillon’s sixpence.

(An interesting side note: The law of karma – being the equivalent of ‘sin’ in Buddhist theology – requires that this stolen sixpence eventually be surrendered, and it can be no coincidence that the narrator winds up paying an unnecessary sixpence at the bazaar’s turnstile in Araby:

I could not find any sixpenny entrance and, fearing that the bazaar would be closed, I passed in quickly through a turnstile, handing a shilling to a weary-looking man.

Thus do the various stories in the Dubliners collection start to inter-connect.)

So An Encounter‘s principle meditation – be it Buddhist, Christian, secular or what have you – is undeniably moral: All actions reap consequence. The final sentences show us a narrator who has truly reaped as he has sown, whose actions in thought, word, and deed have succeeded in forging his friends into monsters – one of which is about to grab him by the ankles. His only hope of escape from the smithy-of-his-soul’s own creation, then, is to return to Mahoney and relinquish to his friend that which he had up to this point so zealously coveted for himself – the title of True Hero:

How my heart beat as he came running across the field to me! He ran as if to bring me aid. And I was penitent; for in my heart I had always despised him a little.

That the nearly forgotten Mahoney with his paltry catapult and boorish ways should wind up charging to the rescue here is perhaps the most touchingly ironic detail of the entire Dubliners collection. No conclusive ending? I say it again – pshaw. The stunning irony here is that Joe Dillon and his ferocious tactics never really vanished at all; the narrator may have tried to write them out of his story, but by the end, he finds himself very much needing them, and much like Little Chandler and Gabriel Conroy, must then endure a profound humbling. An Encounter‘s ending is every bit as powerful as those of A Little Cloud or The Dead – perhaps even more so.

An obvious point: Narrative elisions can be of course filled in any number of ways, and if this reading somehow interferes or conflicts with insights offered in other, alternate readings of An Encounter, then by all means set it aside. I can only reiterate that this is a Reverse-Reading, that these kinds of imaginative insights can only be fostered by Reverse-Reading, and even setting the question of Joyce’s intentionality aside, this particular story now has an uncannily strong narrative cohesion, very much thanks to Reverse-Reading.

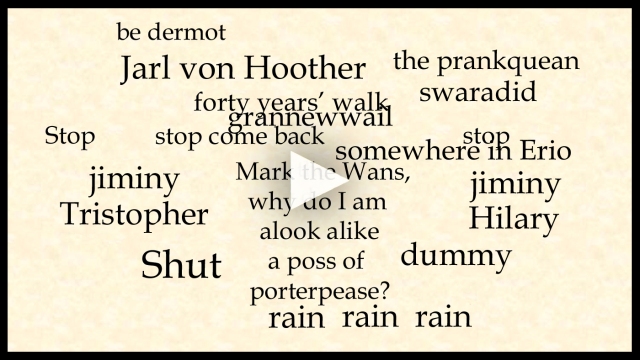

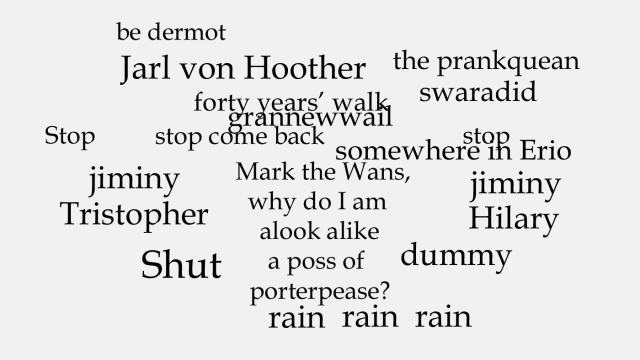

And the Reverse-Reading insights continue. Any Finnegans Wake reader should recognize an early Shem/Shaun study in the diametrically opposed temperaments of the Dillon brothers, and there is a specific Shem/Shaun sub-category that conforms to the Dillon brothers near-perfectly: the Jiminies from the ‘Prankquean’ passage (FW pp. 21-23) which I blogged about a few posts ago. In the ‘Prankquean’, we have a pair of brothers (“Jiminy” = Gemini: twin brothers), one of which is comic (“Hillary” = hilarity), the other tragic (“Tristopher” = Italian/Spanish/Portuguese: triste, sad), along with a third companion, a “dummy”. Each in their turn are “kidsnapped up” (= vanished) by the Prankquean and returned with a difference: Hillary (= Joe) is “convorted” (= converted/distorted) into a “tristian” (= sad christian = Fr. Butler), and Tristopher (= Leo) becomes “provorted” (= perverted/distorted) into a “luderman” (= German: luder man = scoundrel-man / Irish: ludramán, lazy idler = Ringsend pedophile). A third “kidsnapping” is presumably about to be visited upon the “dummy” (= Mahoney, described as “stupid” by the narrator), but is aborted by a thunderclap (= An Encounter‘s shocking finale).

As I demonstrated in “The Prankquean Matrix,” Joyce puts the “rule of three” storytelling trope to very specific use in his works, always casting a female in the role of instigator against a stubborn male protagonist. On the surface, An Encounter appears bereft of any female characters whatsoever, but females are by no means completely absent – the story contains a total of three (!) very striking yet etheric evocations of feminine power:

- “…the peaceful odour of Mrs Dillon was prevalent in the hall of the house.”

- “I liked better some American detective stories which were traversed from time to time by unkempt fierce and beautiful girls.”

- “I watched him lazily as I chewed one of those green stems on which girls tell fortunes.”

These are oddly supernatural descriptions, and I would argue the feminine link to be metempsychotic. The word “metempsychosis” is itself introduced in Ulysses on an absolute tidal wave of feminine imagery in the ‘Calypso’ chapter – a chapter rife with meditations on feminine processes and symbols of feminine power. When asked by Molly to define the word, Bloom turns to a picture of a bathing nymph he has hanging over the bed, and gives a very odd but tellingly associative definition:

—Metempsychosis […] is what the ancient Greeks called it. They used to believe you could be changed into an animal or a tree, for instance. What they called nymphs, for example. (U 4.375)

Typically, Bloom here confuses his concepts – his nymph analogy is much more like metamorphosis than transmigration, but the nymph’s presence here serves Joyce’s overall purpose by permanently associating metempsychosis with the feminine. This imagery in fact builds throughout the novel, so that when we reach Bloom’s hallucination in ‘Oxen of the Sun’ we have a near-literal apotheosis:

And lo, wonder of metempsychosis, it is she, the everlasting bride, harbinger of the daystar, the bride, ever virgin. It is she, Martha, thou lost one, Millicent, the young, the dear, the radiant. How serene does she now arise, a queen among the Pleiades, in the penultimate antelucan hour, shod in sandals of bright gold, coifed with a veil of what do you call it gossamer. It floats, it flows about her starborn flesh and loose it streams, emerald, sapphire, mauve and heliotrope, sustained on currents of the cold interstellar wind, winding, coiling, simply swirling, writhing in the skies a mysterious writing till, after a myriad metamorphoses of symbol, it blazes, Alpha, a ruby and triangled sign upon the forehead of Taurus. (U 14.1099)

Notice how Bloom’s associative cluster links the feminine not just to metempsychosis, but to the very concept of mutable identity, whether it be through transmigration, “myriad metamorphoses of symbol,” or what have you. This is nothing less than a portrait of the Goddess Metempsychosis, the Goddess Metamorphosis, Molly, Milly, Martha, Seaside Girl, Pleiadean queen, etc. By naming her differently at nearly each occurrence – thus making her as formless and mutable as water itself – Joyce gives us the freedom to assign to her whichever epithet we want. ‘Anna Livia Plurabelle’ is the general first choice for most Finnegans Wake readers, particularly when Joyce comes up with a sentence likes this:

—In the name of Annah the Allmaziful, the Everliving, the Bringer of Plurabilities, haloed be her eve, her singtime sung, her rill be run, unhemmed as it is uneven! (FW 104.1-3)

For present purposes I’ll simply call her The Prankquean. Unkempt, fierce, and stunningly beautiful, her matrix is given its very first full expression in Joyce’s canon with An Encounter, which I’ll summarize using the formula I developed in “The Prankquean Matrix“:

- Once upon a time, a thing happens

A young boy (the narrator) seeks adventure. In his words,”I wanted real adventures to happen to myself.”

- As a result, three things happen, one after the other

Exercising his right as author of his own story, he banishes three schoolmates who threaten to usurp his position as chief protagonist.

- The first thing goes POW

He banishes Joe Dillon, who returns as Father Butler via metempsychosis.

- The second thing also goes POW

He banishes Leo Dillon, who returns as the “queer old josser” – again via metempsychosis.

- But the third thing goes BOOM

He banishes Mahoney, who returns to the rescue as “Murphy” – via metamorphosis.

- And now it’s a new thing

Penitence.

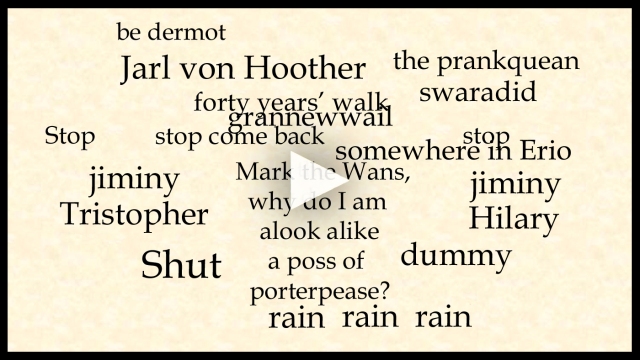

I’ll let Joyce himself have the final word here. As you either watch the following video or read Finnegans Wake pp. 21-23 (on which it is based), consider how the events of An Encounter are echoed in its narrative:

The ‘Prankquean’ Video – by JoyceGeek

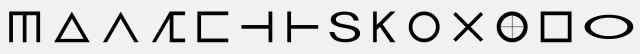

One can think of these glyphs quite literally as “characters” – not only in their typographical sense: e.g. “280 characters per tweet max,” but in their dramatic sense as well: i.e. “players in a story.” For the record, Wake scholars generally refer to them as sigla, a plural Latin word basically meaning “characters.” Its singular form is siglum.

One can think of these glyphs quite literally as “characters” – not only in their typographical sense: e.g. “280 characters per tweet max,” but in their dramatic sense as well: i.e. “players in a story.” For the record, Wake scholars generally refer to them as sigla, a plural Latin word basically meaning “characters.” Its singular form is siglum.

[Imagine] a series of billiard balls in close contact: if another ball is rolled against the last stationary ball, the moving ball will stop dead, and the foremost stationary ball will move on. Here precisely is Buddhist transmigration: the first moving ball does not pass over, it remains behind, it dies; but it is precisely the movement of that ball, its momentum, its karma, and not any newly created movement, which is reborn in the foremost ball. […] Nothing is transmitted but an impulse, a vis a tergo, dependent on the heaping up of the past. It is a man’s character, and not himself, that goes on.

[Imagine] a series of billiard balls in close contact: if another ball is rolled against the last stationary ball, the moving ball will stop dead, and the foremost stationary ball will move on. Here precisely is Buddhist transmigration: the first moving ball does not pass over, it remains behind, it dies; but it is precisely the movement of that ball, its momentum, its karma, and not any newly created movement, which is reborn in the foremost ball. […] Nothing is transmitted but an impulse, a vis a tergo, dependent on the heaping up of the past. It is a man’s character, and not himself, that goes on.